2017 Participant Newsletter

Women's Health Australia

It has been a busy year at Women’s Health Australia with a number of exciting projects underway. This edition marks the official launch of our updated brand. It’s only fitting that you, our participants, are the first to see the study’s updated logo and fresh, polished look. You can read more about changes to our look in this newsletter.

In 2017 your data continued to make an impact on the health and wellbeing of Australian women (see the feature on mental health for new mums). It is incredibly gratifying to see the work done at the study, and by our research collaborators resulting in tangible changes to women’s health policy, guidelines and clinical practice.

In September, the Minister for Health, Greg Hunt, announced a further three years funding for the study as part of the government’s continued investment in women’s health initiatives. This is a wonderful outcome that recognises the importance of the study, and your data, as researchers and policymakers tackle the big health issues of the next 20 years.

With thanks,

Professor Gita Mishra – University of Queensland and Professor Julie Byles – University of Newcastle (on behalf of the Women’s Health Australia team)

Upcoming surveys

- May 2018 – 1973-78 cohort Survey 8 and MPreM Study

- May 2018 – 1921-26 cohort Survey 14

- November 2018 – 1921-26 cohort Survey 15

Contacts

Phone: 1800 068 081

Website: www.aslwh.org.au

Refreshing our

Brand

Women’s Health Australia celebrated its 21st birthday with a makeover. We’re excited to have a new look that reflects the high quality of our research and the study’s position as a National Research Resource.

It's your loyalty to the study over the past two decades that has enabled our success. Clearly, it's important that you recognise us when the next survey arrives, so we haven’t strayed too far from our roots. The 'brush stroke' is still a part of the logo and we have kept a softened version of the familiar green and purple colours. You will notice that we use 'Women's Health Australia' alongside the longer, official study name 'Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health.'

You will see updates on the website, social media and in our print materials throughout 2018. Our website address and email addresses will also change from www.alswh.org.au to www.womenshealthaustralia.org.au. Both versions of the web address will continue to work if you need to get in touch.

The biggest change will be for women recruited in 2013 through the Women’s Health of Australia (WHoA) campaign as the old WHoA logo is retired.

New Mums' Mental Health

Making a difference

The perinatal period (from conception to one-year post birth) is a challenging time in most women’s lives. The information shared by the 1973-78 cohort, both in surveys and in a 2011 substudy, has been used to better understand the emotional health issues facing new mothers, to assess programs like the National Perinatal Depression Initiative, and contribute to practical tools and guidelines.

The substudy revealed that women who were screened for depression were more likely to be referred to mental health and other support services during pregnancy (19.0% vs. 3.7%) and in the first year postpartum (20.7% vs. 4.0%) than those who weren’t screened. Importantly, distressed women who were asked about their mental health by clinicians were more likely to seek help. A key finding was the disparity in care between patients in the public and private systems. Routine depression screening and psychosocial assessment is widely implemented in Australia. However, women choosing private maternity care were three times less likely to be screened than women delivering in the public sector.

As a direct result, Dr Marie Paule-Austin and Dr Nicole Reilly who were involved in the substudy, went on to collaborate with health insurer BUPA to develop mummmatters, an online tool for assessing perinatal mental health. In addition, research based on the data shared by the 1973-78 cohort was cited in Mental Health Care in the Perinatal Period: Australian Clinical Practice Guideline. And, in an important shift towards prioritising perinatal mental health, the Australian Government announced changes to Australia’s Medicare Benefit Schedule (MBS) items for obstetric services. The proposed changes include a requirement that a mental health assessment, including screening for substance abuse and domestic abuse, be provided as part of pre and postnatal care.

Don't

Stress

Type 2 diabetes is a serious condition in which the body becomes resistant to insulin and can’t properly regulate glucose (sugar) in the blood. It is the second most common disease affecting our society and is increasingly common in younger adults. Diabetes can be well managed with positive lifestyle changes and adherence to diet and medication. However, if not well managed the long-term complications can be serious and include blindness, kidney failure, limb amputation, heart attacks and stroke.

Type 2 diabetes is considered a lifestyle disease, with modifiable risk factors. This means that you can reduce your chance of getting diabetes by being a healthy weight, being physically active and not smoking. But there are other, potentially more important factors at work. Psychological stress is increasingly being considered as a risk factor for chronic disease and data from the 1946-51 cohort has been used to investigate the links between stress and diabetes.

Researchers found that compared to those with no stress, women who reported minimal levels of stress had 1.6 times the risk of being diagnosed or treated for diabetes three years later. In women with moderate to high levels of stress, the risk was 2.3 times higher.

The researchers then delved deeper to examine how much of the link could be explained by the impacts of stress on other diabetes risk factors. They found that other factors like body mass index (BMI), hypertension, and physical activity explained only 10% of the diabetes risk in women with minimal levels of stress and 20% in women with moderate to high levels of stress. This means that perceived stress is a strong risk factor for diabetes in its own right.

Harris ML, Oldmeadow C, Hure A, Luu J, Loxton D, et al. (2017) Stress increases the risk of type 2 diabetes onset in women: A 12-year longitudinal study using causal modelling. PLOS ONE 12(2): e0172126.

Trigger warning:

This article is about violence. If you or someone you know has been impacted by violence, support is available from DV Hotline ( www.1800respect.org.au) or Lifeline (131114).

If you or someone you know is in imminent danger, please call 000.

#MeToo:

Disclosing abuse

In 2017 the combined media power of Hollywood’s leading actresses finally shone a spotlight on sexual abuse and violence against women. By asking women to post their experiences on Twitter with the tag ‘#MeToo’, actress Alyssa Milano propelled a grassroots campaign into a global movement shared by millions. Time Magazine’s 2017 Person of the Year was awarded to the Silence Breakers, a group of courageous women (some famous, some anonymous) who spoke out about sexual abuse in their industries. Oprah Winfrey’s passionate Golden Globes speech expanded the #MeToo spotlight to encompass the many types of abuse experienced by women from all walks of life. In Australia, Rosie Batty has worked hard to publicly highlight the tragic consequences of domestic violence. And for 22 years, you, the women who make up Women’s Health Australia have been quietly, anonymously, taking part in your own #MeToo movement by sharing your experiences.

To really address the complexity of violence against women, we need more than social media and awards night speeches. We need to document when and where abuse occurs, the risk factors that leave women vulnerable to violence, and information about what might promote recovery from these experiences.

During 2017, your information was used to highlight the detrimental impact of bullying on young women’s health and to demonstrate the long-term physical and mental health impacts of domestic violence. The Department of Social Services also commissioned a report to find out why women respond inconsistently to questions about domestic violence, sometimes reporting experiences of domestic violence in one survey, then reporting no experiences in later surveys.

One hundred and thirty-four women from the 1989-95, 1973-78 and 1946-51 cohorts took time to participate in interviews about their responses to survey questions on abuse experiences. We found that asking women to respond accurately to questions about abuse can involve revisiting past trauma, triggering undesirable emotions, unresolved inner conflicts, and threats to past and current self-identity. For some women, these costs are too high, leading to inconsistent responses over time. Nevertheless, women who took part in interviews also said providing such information will help others, so the costs of providing sensitive information were counterbalanced by the potential benefits to others. Further investigation will find methods to reduce the risk of re-traumatising women who have lived with violence.

We want to take this opportunity to honour the courage and openness of the women who took part in those interviews and to all of you who have taken the time and emotional energy to complete the more stressful items included in the Women’s Health Australia surveys, we sincerely thank you for your generosity. The information you have provided has been pivotal to the development of the current Women’s Health Policy and continues to provide the evidence needed to design effective prevention and recovery programs.

Bullying Hurts Adults Too

Over half of 18-23-year-old women have experienced bullying in the past.

One in five 18-23-year-old women were bullied recently.

These shocking figures come from the 1989-95 cohort’s 2013 survey. The women who experienced bullying reported worse general health and higher levels of psychological distress. They were also more likely to smoke, take illicit drugs and be overweight or obese. Most concerningly, more than half of the women who had been recently bullied felt as though life was not worth living, and one-third had self-harmed.

Australia’s prevention and treatment programs currently target school children with little support for adults. This is the first time researchers have looked at the extent of the issue in young Australian women outside of an educational or industry-specific context. The information you provided has highlighted the scale of the problem and the need for services for women who have experienced bullying.

If you need help please contact Lifeline on 13 11 14. In an emergency call 000.

Townsend, N., Powers, J. and Loxton, D. (2017), Bullying among 18 to 23-year-old women in 2013. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 41: 394–398.

Raising Kids in the Digital Age

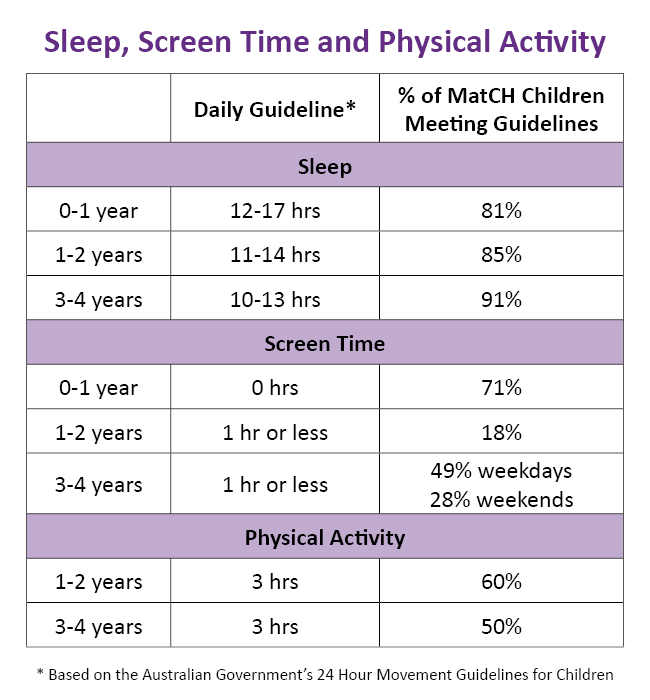

The Australian Government recently released the 24 Hour Movement Guidelines. These evidence-based recommendations are for children from birth to five years old. Parents and caregivers are encouraged to use the guidelines when they structure daily routines around sleep, screen time and physical activity. Of course, everyone’s circumstances are different and a child’s home environment, how they use mobile technology, and what else they do with their day are important factors.

Last year over 3000 mothers from the 1973-78 cohort took part in the Mothers and their Children’s Health (MatCH) substudy, completing surveys on nearly 6000 girls and boys (Thank you!). We examined initial data from the substudy to see how children in the substudy compare to the guidelines.

Screens are firmly entrenched in our children’s lives; 9% of 3-4-year-olds and 36% of 5-12-year-olds had mobile devices in their bedrooms. Many children exceeded the recommendations for screen time. Data also show that children in the MatCH study had more screen time on weekends. But, it’s important to remember that educational and shared activities using screens can be beneficial for development and relationships.

About half of younger children met the guidelines for physical activity, but this dropped off as they got older. However, most children in the substudy met the guidelines for sleep. And, even though this is the digital age, 90% of children still had more than 30 children’s books in their home.

What do the mothers of MatCH say?

“I find the screen time hard to judge, I believe in everything in moderation so don't 'clock' hours. It can be on but they are building a cubby house while watching a show!”

“I think you should be careful with interpreting information regarding screen time. Like all activities, too much screen time can be a negative influence, however, there are also lots of great screen time activities which, if engaged within a positive and supervised way, can be incredibly beneficial both socially and academically. Smart devices are not going to go away, and I don't believe that classifying them in a negative way is a constructive way to teach our children to make use of them.”

“Physical activity really varies according to weather – our region has had a very hot summer. Screen time - enforcing limits is a significant contributor to family stress.”

Visit www.health.gov.au for more information about the guidelines.

Visit www.alswh.org.au/match for more information about the substudy.

Hormone Replacement Therapy

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is a hot topic for menopausal women. At its peak in 2001, 33% of the 1946-51 cohort were prescribed HRT. Use dropped in 2002 after a highly publicised trial linked HRT to breast cancer. However, recent research suggests HRT might actually have health benefits for some groups of women.

We turned to the women of the 1946-51 cohort for answers. Researchers investigated whether there was a link between the menopausal stage when women started HRT, their overall risk of death (known as all-cause mortality), and their risk of death from cardiovascular disease. The menopausal stages included pre-menopausal, going through menopause, or hysterectomy/oophorectomy (removal of ovaries). Hysterectomies and oophorectomies are very common; one-third of the 1946-51 cohort had this procedure by their early-to-mid 60s.

In good news, women with a hysterectomy/oophorectomy who took HRT had a 53% reduced risk of death from cardiovascular disease. There was no apparent effect on mortality risk or cardiovascular disease for women who took HRT during or after natural menopause. We are planning further research to investigate the protective effects of HRT. If you are considering HRT please consult your doctor.

Chen L, Mishra GD, Dobson AJ, Wilson L & Jones MA. (2017). Protective effect of hormone therapy among women with hysterectomy/oophorectomy, Human Reproduction, 32(4), 1: 885–892.

Salutogenesis

Creating health and ageing well

Two different approaches to analysing data show how women in the 1921-26 cohort are ageing well.

Dr Lucy Leigh analysed survey responses to see how older women’s physical abilities changed between the ages of 73-78 and 85-90. As women aged they fell into one of four groups.

Group 1: About 14% of women maintained high levels of physical function between the ages of 73-78 and 85-90.

Group 2: Another 30% started at a high level and declined over time. However, they were still able to undertake most daily activities and get around even in their late 80’s.

Group 3: Around 40% women started at a lower level, and their abilities declined to a point where most had difficulty with most activities.

Group 4: Around 16% of older women started with poor levels of physical function. Over time, this declined to a point where they had difficulty dressing, bathing and moving around within the home.

Overall, the proportion of women who needed help with daily tasks increased from 9% to 34%. Even so, many of these women continued to provide care for someone else’s health needs into their late 80s and early 90s.

To understand how women adjust to changes in their later years, Dr Robyn Kennaugh studied comments they wrote on surveys. Women described many challenges, including caring for their husband or other relatives, the loss of their spouse, and changes to their health. While caring for their partner was physically and emotionally difficult, the subsequent loss was a significant source of stress in a woman’s life.

However, the women also described resources that helped them meet these challenges, including inner strength, and the support of others. Women wrote how they derived help, not just from families and friends, but also from peers, doctors, health services, and community organisations. They described the importance of a positive disposition to help live with their loss. They wrote that they took initiative to ‘do for themselves’ what no one else could. These positive responses help women reorient to a new stage of life, and continue to engage in meaningful activities and experience wellbeing.

The women had less success adapting to changing social circumstances, including managing finance, accessing transport and finding suitable housing. These are areas where women may need to ‘lean on others’ more, and where health providers and support networks need to be aware of the need for balance between offering support and allowing women to preserve their independence in later life.

Get your Free Health Check

Menstruation to PreMenopause substudy

Some women in the 1973-78 cohort will soon be invited to take part in a new substudy called Menstruation-to-PreMenopause (M-PreM). Our goal is to understand how a woman’s reproductive history (from their first period to mid-age) influences their risk of developing chronic diseases and poor health. We will be combining your survey data with clinical and genetic data.

During a visit to a pathology clinic, women taking part in this substudy will be asked to give a small blood sample (about a tablespoon) and to do a range of measures and tests including blood pressure, heart rate, body measurements, cognitive function, hand grip strength, and lung function. They will also have the opportunity to wear a small physical activity monitor for one week and keep a sleep diary. The data collected during the clinic visit will be used to help understand women’s health and wellbeing before they enter the menopause transition.

Improving Health and Healthcare Services for Australian Women

Background

You may remember that during this project we have asked you for permission to receive details from Medicare Australia about your use of Medicare-funded health services. By putting the Medicare data together with the survey data, we have looked at general patterns of use of health services, particularly general practitioner and specialist consultations. Having these data has helped us to write reports about women’s access to health services and particularly about how much the services cost according to where women live around the country. These reports have been provided to the government to help improve services for women.

What’s new?

Following discussion with Medicare Australia, information held by them will be regularly provided to the research team without your needing to consent every time. Other information, such as birth and death records, disease registers and hospital discharge records, aged care and community datasets, will also be available subject to strict privacy and confidentiality rules. Names and addresses are not included with the information. The project staff who analyse these datasets and the survey data have signed confidentiality statements and they have no information in the datasets that could identify an individual person. This research is conducted in accordance with relevant privacy requirements and other legislation protecting this information.

What happens next?

You do not need to do anything. However, if you have any questions about this process or if you need more information, please call the Freecall number 1800 068 081and we will send you a more detailed information sheet. If you have concerns about this method of data collection, you can opt out of this by phoning the Freecall number. We will provide updates in future newsletters about our progress and findings and how this research will benefit the health of women now and in the future.

If we do not hear from you after inviting you to complete your latest survey we will send reminders. These may include reminders targeted to participants by matching your email address or mobile phone number with social media records in a secure and confidential manner. If you do not wish to be contacted in this way please let us know by phoning the Freecall number 1800 068 081. Your participation in the project is voluntary.

If you have any concerns about this project and would prefer to discuss these with an independent person, you should feel free to contact the Human Research Ethics Officer at either the University of Newcastle or University of Queensland.

The Human Research Ethics Officer Research Branch, The University of Newcastle, University Drive, Callaghan, NSW 2308

Ph: 02 4921 6333

The Human Research Ethics Officer, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072

Ph: 07 3365 3924

The research on which this newsletter is based was conducted as part of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health by the University of Queensland and the University of Newcastle. We are grateful to the Australian Government Department of Health for funding and to the women who provided the survey data.