2018 Participant Newsletter

Women's Health Australia

Women's Health Australia (officially the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health) is now entering its third decade. This fantastic achievement would not be possible without you, our participants.

In 2018, your survey answers helped to advise policymakers on a range of health topics. They also helped to improve our understanding of women's health across the life course. We can only highlight a handful of recent results here. You can read summaries of all the latest research in our annual reports at: www.alswh.org.au/publications-and-reports/annual-reports.

With thanks,

Professor Gita Mishra – University of Queensland and Professor Julie Byles – University of Newcastle (on behalf of the Women’s Health Australia team)

Surveys

Participants born from 1973-78, if you haven't done your survey you still have time!

Visit: http://www.alswh.org.au/for-participants/1973-78-cohort

Upcoming Surveys

- April 2019: 1989-95 cohort Survey 6

- May 2019: 1946-51 cohort Survey 9

- May 2019: 1973-78 M-PreM Substudy

Contacts

Phone: 1800 068 081

Website: www.alswh.org.au

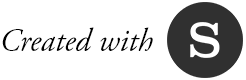

Menarche to Pre-Menopause

(M-PreM) Substudy

In the next 12 months, we will invite the 1973-78 Cohort for a free health check as part of the M-PreM substudy.

The substudy will look for links between reproductive characteristics – like the age you had your first period (menarche) and painful or heavy periods – and poor health and chronic disease before menopause.

Participants will visit a clinic to do some simple physical tests and give a blood sample. They will get to wear a physical activity monitor for eight nights.

To find out more, go to www.alswh.org.au/m-prem

Your information in action

Over the past year, research based on your survey responses was included in:

International evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) 2018

PCOS is a complex disorder with reproductive, metabolic, and psychological features, making it hard to diagnose and treat.

Senate Inquiry into Sleep Health in Australia

Our report outlined how life events and other factors affect sleep health and the impact on health and wellbeing. You reported sleep issues during pregnancy and motherhood, menopause, and in older age. Sleeping difficulties were linked to poor mental health, disease, falls, and accidents.

Senate Inquiry on the Future of Stillbirth Research and Education in Australia

The study’s submission highlighted issues accessing stillbirth data from the different states and the research currently underway using your data.

Senate Inquiry into the Obesity Epidemic in Australia

Your data shows that even though women are aware of public health messages, we are not meeting guidelines for exercise and nutrition, and our weight loss attempts are mostly unsuccessful. Our submission pushed for better support of women’s efforts. It also highlighted new research from the Mothers and their Children’s Health (MatCH) substudy. Researchers found that obese women were more likely to have obese children.

Read the latest Inquiry submissions at www.alswh.org.au/publications-and-reports/submissions

Improving quality of life

With even a little exercise

Exercise is about more than just losing weight. Active women have a better quality of life. Research from the 1946-51 Cohort shows that women’s quality of life improved as their activity levels increased.

Importantly, it didn’t matter whether women were in the obese, overweight, or healthy Body Mass Index (BMI) weight range. They still benefited. The biggest difference in quality of life was between women who did no exercise, and women who did just a little. However, getting more exercise was definitely better. Being highly active (for example doing vigorous running or cycling for more than 2.5 hours each week) could help to offset the impact of obesity. Highly active women in the obese BMI range had the same quality of life as women in the healthy and overweight range with low activity levels.

If you can, it’s well worth adding a few extra minutes of physical activity to your week.

Published in Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health (2018) https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12802

Eat the rainbow to keep the doctor away

Did you know that women’s Medicare costs go down as the variety of vegetables they eat each week goes up?

Researchers looked at links between diet quality, and the number and cost of Medicare claims made by the 1946-51 Cohort over ten years. For every extra type of vegetable eaten each week, women who were a healthy weight made 1.9 fewer Medicare claims and were charged $139 less. The charge is the total of the Medicare benefit plus any gap fees. Women in the overweight BMI range made 2.3 fewer claims and were charged $176 less, and women in the obese BMI range were charged $235 less.

Public health strategies that encourage us to eat more vegetables could result in considerable health care savings for the government and us.

Published in Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics (2018) https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12556

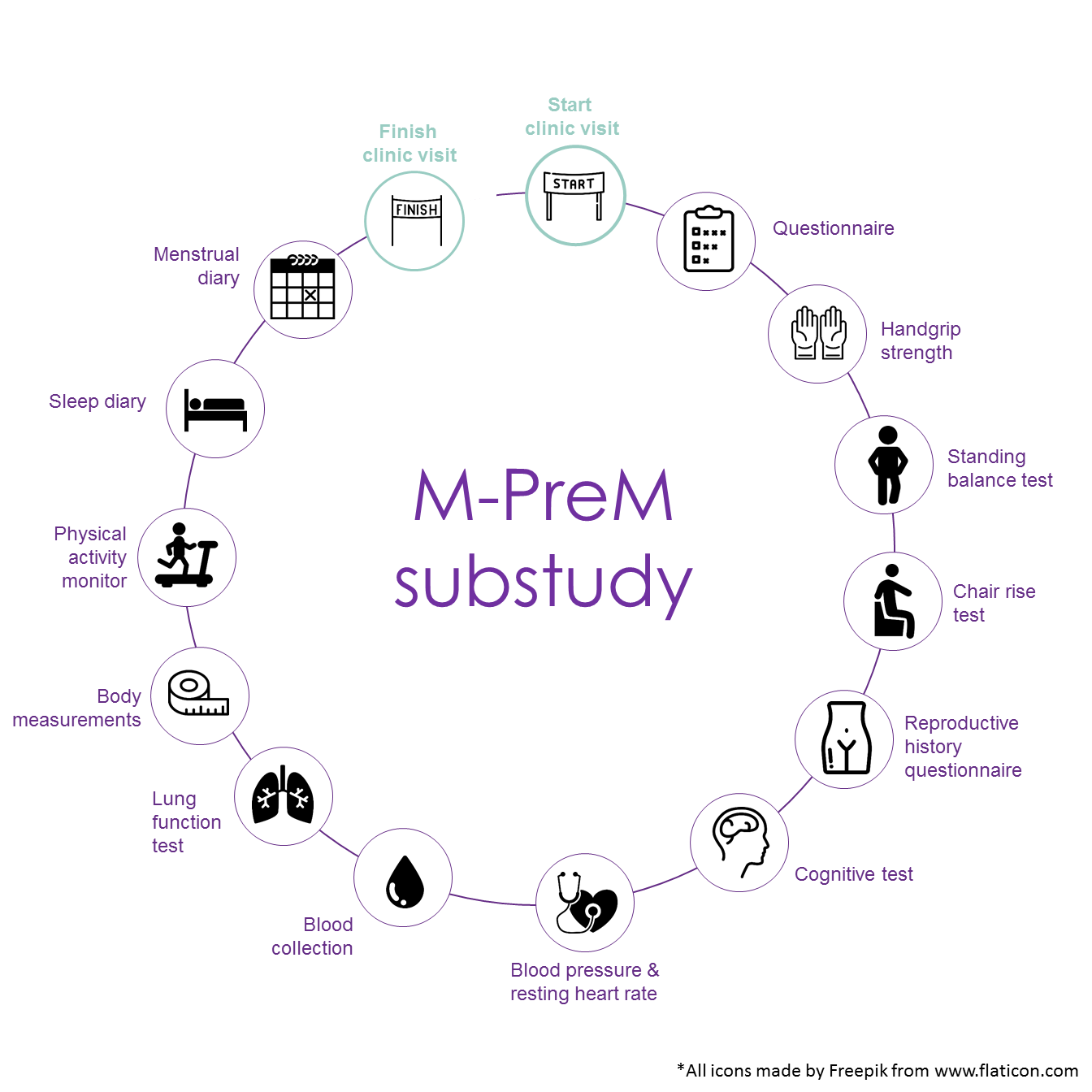

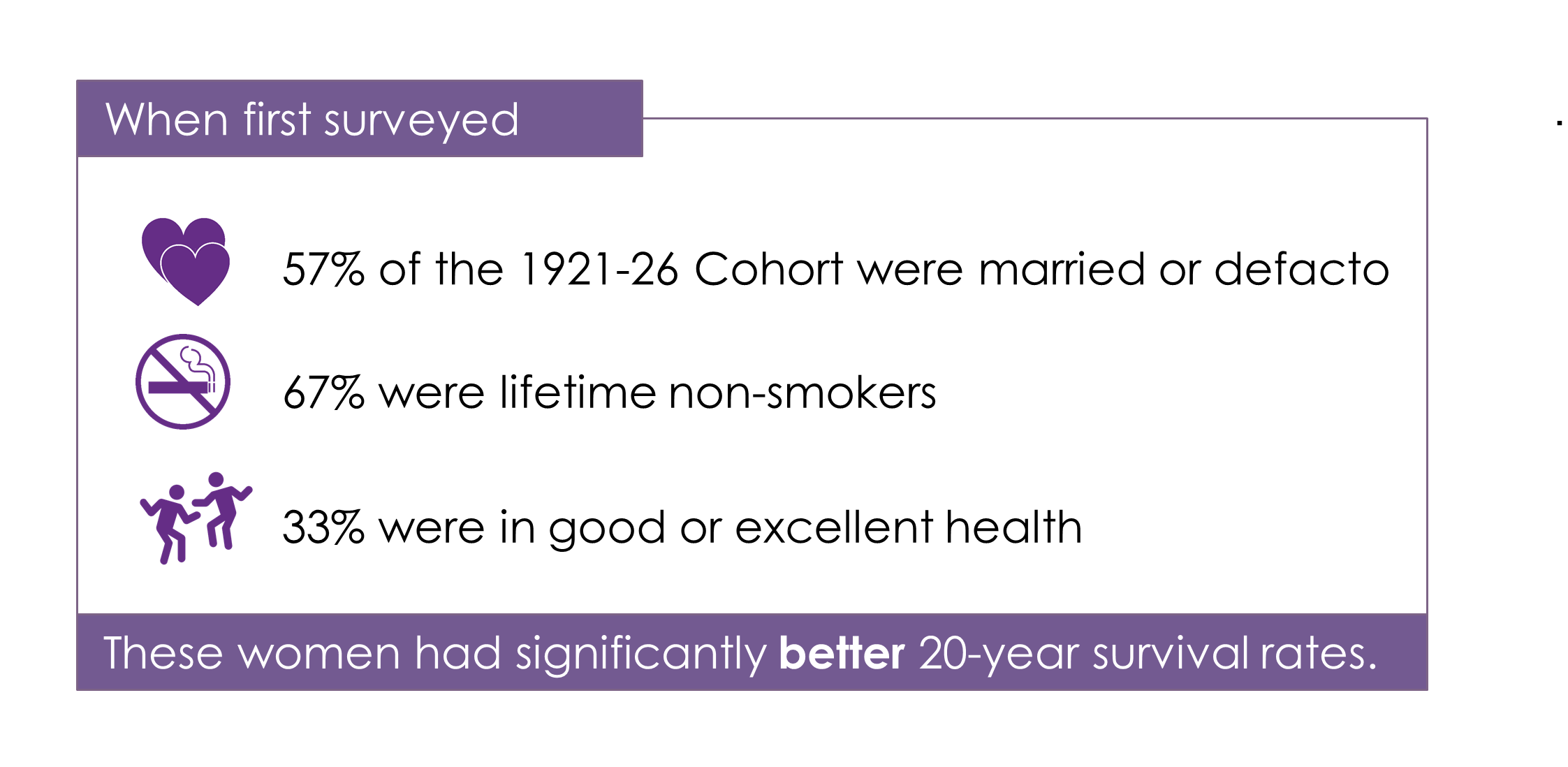

What determines a long life?

Healthy behaviours play a large part in determining how long we live.

In 1996, 12,432 women born between 1921 and 1926 completed their first survey. The 876 exceptional women who remain in the study at age 92-97 have a good chance of surviving into their 100s.

At their last survey in May 2018:

- Over 55% said their health was good, very good or excellent

- Over 60% lived alone, 9% with a spouse or partner, 11% with their children and 4% with other family members

- 26% were still driving

- 13% had no problems carrying their own groceries

- 20% felt full of life all or most of the time

- Over 60% thought they were a happy person most or all of the time

From childcare to elder care:

2018 Major Report to Australian Government Department of Health

At some point, the majority of women will become a caregiver for a family member or friend.

In our 2018 major report to the Government, we looked at women’s roles as unpaid caregivers and the impact on their health and wellbeing, including reviewing your survey comments. Your comments were both heartwarming and heart wrenching and helped to humanise the statistics by demonstrating the needs, coping strategies, strength, resilience, and love of caregivers.

As circumstances change, women move into and out of caregiving roles. In their 20s and 30s, only 6% of the 1973-78 Cohort cared for another adult. Through their 50s and 60s, roughly 60% of the 1946-51 Cohort cared for another person at some point. While 25-30% of the Cohort identified as carers at any survey, only 4% of the women provided care at every survey. Women who lived with an adult they cared for tended to report greater stress, poorer health, and more difficulty managing on their income than those who cared for someone outside the home or who did not have a caregiving role.

“My husband had a stroke over ten years ago. I have been looking after him. He is 83 in May. He has gone from walking stick to a frame to a wheelchair. He can just move along with me holding him and it is getting harder every day. I’m not complaining, he’s my love.”

For older women, providing care becomes more challenging and demanding as they increasingly need care and support themselves. At age 79-84, one in 10 women living with someone they cared for also required care themselves. While women expressed gratitude for services and support, they also showed a reluctance to ask for help. They felt it was a sign that they had failed, and were concerned about the consequences of intervention. Women said: “I don’t want to put my husband in a home.” If their husband did go into permanent residential care, their caregiving role continued. Caregiving was often mutual, and many older women who outlived their husbands talked about the loss of the person who cared for them on a daily basis.

Informal (unpaid) caregiving is generally defined as caring for people who are ill, disabled, or frail. In this report, we broadened the definition to include care for children.

Four out of five women from the 1973-78 Cohort had at least one child by age 37-42. Overall, they relied far more heavily on informal childcare (family and friends) than formal childcare (e.g. long day care, after-school care). At age 28-33, 75% of mothers from this Cohort used childcare; 20% only used formal childcare services, 28% just used informal childcare, and a further 26% used a mix of both. The cost of formal childcare was a problem for 30% of women.

While most were happy with their share of childcare, up to 27% wanted ‘other family members to do more’. Common themes in your survey comments were the exhaustion of managing a household and being a mother, wife, or partner, and for some, an employee. Many women commented on the sacrifices they made to return to paid work; in either the type of job, hours worked, or money earned.

“There are questions about work and work life balance. My situation is that I have recently stopped paid work as I found it impossible for both my husband and myself to maintain careers and have the level of involvement in our children’s lives that we wanted. The lack of flexibility in mid-level corporate jobs mean that for many people it is a choice of all (full-time) or nothing. The inability for me to maintain my career has led to dissatisfaction and worry about our financial future, especially as I am no longer financially independent.”

Grandparents remained the main source of informal childcare in Australia. Sixty per cent of the 1946-51 Cohort (in their mid-60s) and 12% of the 1921-26 Cohort (at ages 85-90) regularly looked after their grandchildren. For half of the 1946-51 Cohort, this was on top of their own work commitments. Despite this, 90% of those caring for their grandchildren were happy with their share of the childcare duties.

Sandwich generation caregivers look after a child or grandchild plus a partner or ageing parent. The additional burden of care has an impact on their physical and mental health. At age 37-42, 11% of the 1973-78 Cohort were sandwich caregivers. This was higher in the 1946-51 Cohort at age 65-70, with 25% being sandwich caregivers. Generally, women who provided childcare as well as caring for someone they lived with had poorer health outcomes than those providing other types of care. At age 79-84, 10% of the 1921-26 Cohort cared for multiple generations. These women are able to provide this level of care because they had better health than their peers.

“There are questions about work and work life balance. My situation is that I have recently stopped paid work as I found it impossible for both my husband and myself to maintain careers and have the level of involvement in our children’s lives that we wanted. The lack of flexibility in mid-level corporate jobs mean that for many people it is a choice of all (full-time) or nothing. The inability for me to maintain my career has led to dissatisfaction and worry about our financial future, especially as I am no longer financially independent.”

Read the full report at www.alswh.org.au/publications-and-reports/major-reports

Focus on your health before pregnancy

Women are usually told to make diet and lifestyle changes during pregnancy, for example, quitting cigarettes and alcohol, taking vitamin supplements, and watching their weight. However, research suggests that it is better to make changes to our health and diet long before we get pregnant. Staying a healthy weight and eating well in the months and years leading up to pregnancy can reduce the risk of complications like gestational diabetes, high blood pressure, and pre-eclampsia. Higher physical activity levels before conception were linked to lower risks of pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes.

The 1989-95 Cohort will be the next generation of mothers. Forty-three percent are in the overweight or obese BMI weight range. Thirty percent have low levels of physical activity or are inactive. Twelve percent meet the nutrition guidelines for vegetables. Globally, 60% of births are unplanned. Australians are not alone in needing education and support programs to improve our health. Researchers suggest that the best time is during our teenage years when many unhealthy habits like smoking, drinking, and poor nutrition begin. Whether or not we go on to become parents, staying a healthy weight, exercising, and eating well have life-long benefits.

Published in The Lancet (2018) https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30311-8

Mental health can predict future

physical health

People with mental health conditions are also more likely to have a chronic physical condition like diabetes, cancer, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, asthma, or bronchitis. Researchers looked at the 1973-78 Cohort to see if women’s mental health in their 20s was linked to health conditions in their 30s. The women’s mental health followed one of five pathways. They could be grouped as always good, always poor, getting better over time, getting worse over time, or getting worse and then better. Around 6% of the cohort always had poor mental health in their 20s. Another 5% got worse over time. Women in these groups were more likely to develop a chronic physical condition in their 30s. We don’t fully understand how mental health symptoms contribute to the development of physical conditions. However, if you are experiencing mental health problems it is important to ask for help. You should also talk to your GP about ways to reduce your risk of developing other health conditions.

Published in Journal of Affective Disorders (2019) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.106

Who uses aged care services?

The number of people needing aged care is expected to double in the next 20 years as the baby boomers enter old age. Governments need an evidence base to make decisions on policy and programs for funding. However, information about how women use aged care is lacking.

Researchers identified four patterns of aged care use when the women from the 1921-26 Cohort were 75-90 years old. A large number (41%), were not likely to use any services until age 85, and only a few services after that. Another 24% had a long period of community care use (provided by HACC/CACP as available at that time). The third group (11%) moved from using community care services to being in residential aged care (RAC) by age 82-87. More than half remained in RAC for at least three years (to age 85-90). The fourth group (24%) had a pattern of earlier mortality (all died by age 82-87), with many using different services over their last few years.

Your survey answers tell us that there should be a focus on helping women remain independent in the community and helping them to maintain their abilities through health promotion and re-ablement activities. Many women will need RAC once their needs increase beyond what their community can offer. RAC should not be seen as a worse option than community care, but as an option for meeting different needs at a later part of life. Given older women were in RAC for a long time, it must become a place for living, with a focus on lifestyle and quality of life.

Published in Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics (2019) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.11.010

Vaping

What is it and who does it?

Smoking electronic cigarettes or e-cigarettes is called vaping. It is quickly growing in popularity. However, there are worries about the effects of nicotine and other ingredients in the vaporised flavourings. More than one in 10 young women from the 1989-95 Cohort have tried vaping. It is often marketed as a way to quit tobacco products. In this age group, current smokers were 10-times more likely to use e-cigarettes than non-smokers were. Ex-smokers were five-times more likely to use e-cigarettes. Over a quarter of the e-cigarette users had never smoked tobacco. This seems good, but e-cigarette users are more likely to go on to smoke tobacco. E-cigarette users were more likely to be younger, live in urban areas, drink more than two standard drinks a day, or have money troubles. Women who had experienced domestic abuse were also more likely to have tried using e-cigarettes at some point.

Published in American Journal of Preventive Medicine (2019) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.09.019

Improving Health and Healthcare Services for Australian Women

Background

You may remember that during this project we have asked you for permission to receive details from Medicare Australia about your use of Medicare-funded health services. By putting the Medicare data together with the survey data, we have looked at general patterns of use of health services, particularly general practitioner and specialist consultations. Having these data has helped us to write reports about women’s access to health services and particularly about how much the services cost according to where women live around the country. These reports have been provided to the government to help improve services for women.

What’s new?

Following discussion with Medicare Australia, information held by them will be regularly provided to the research team without your needing to consent every time. Other information, such as birth and death records, disease registers and hospital discharge records, aged care and community datasets, will also be available subject to strict privacy and confidentiality rules. Names and addresses are not included with the information. The project staff who analyse these datasets and the survey data have signed confidentiality statements and they have no information in the datasets that could identify an individual person. This research is conducted in accordance with relevant privacy requirements and other legislation protecting this information.

What happens next?

You do not need to do anything. However, if you have any questions about this process or if you need more information, please call the Freecall number 1800 068 081 and we will send you a more detailed information sheet. If you have concerns about this method of data collection, you can opt out of this by phoning the Freecall number. We will provide updates in future newsletters about our progress and findings and how this research will benefit the health of women now and in the future.

If we do not hear from you after inviting you to complete your latest survey we will send reminders. These may include reminders targeted to participants by matching your email address or mobile phone number with social media records in a secure and confidential manner. If you do not wish to be contacted in this way please let us know by phoning the Freecall number 1800 068 081. Your participation in the project is voluntary.

If you have any concerns about this project and would prefer to discuss these with an independent person, you should feel free to contact the Human Research Ethics Officer at either the University of Newcastle or The University of Queensland.

The Human Research Ethics Officer Research Branch, The University of Newcastle, University Drive, Callaghan, NSW 2308

Ph: 02 4921 6333

The Human Research Ethics Officer, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072

Ph: 07 3365 3924

The research on which this newsletter is based was conducted as part of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health by the University of Queensland and the University of Newcastle. We are grateful to the Australian Government Department of Health for funding and to the women who provided the survey data.